There are different ways to fight for peace – one of them was proposed back in the 19th century by the Belgians Paul Otlet and Henri Lafontaine. Information and its accessibility to everyone is what they believed would lead mankind away from military conflicts toward the idea of uniting for the sake of knowledge, for the sake of a common movement toward progress and enlightenment. Otlet and Lafontaine came up with an amazing project that indeed united many and many people, but, alas, was destroyed by war. It is a good hypothesis, for even now education and information are the most valuable resource. Fortunately, in today’s world we can obtain and adjust our knowledge from different resources. Students don’t often go to paper libraries because Editius comes to their aid.

How did the one-of-a-kind repository of information come into being?

One can read and listen as much as one wants about the atmosphere in which Europeans of the late XIX century were, an atmosphere of changes which affected all areas of life, but to imagine how it was in reality is not so easy for a modern person. One has to be content with individual illustrations to complete the overall picture. Art Nouveau, the revolution in various fields of scientific knowledge, political transformations, social transformations – the directions of change were enough for some private initiatives to get lost – though they managed to get a serious resonance in their time.

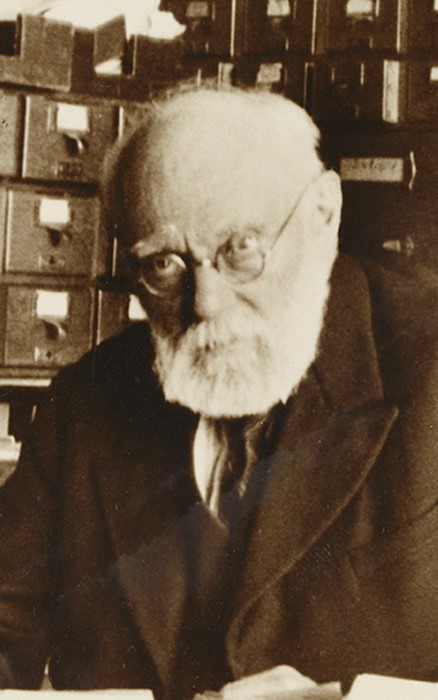

Few contemporary Internet users know the name of Paul Otlet, who, incidentally, not only foresaw serious transformations in the information life of society, but participated in their preparation. And all because one day he, the son of a successful businessman and a successful lawyer, who had received an excellent education and an excellent start in his career, nevertheless decided to devote himself to the science of bibliography – the one related to information management, catalogs, lists, descriptions of books and other written and printed sources.

Born in Brussels in 1868, Paul Otlet studied, incidentally, at home until the age of 11 – teachers were hired for him; his father considered school unsuitable for his son. Subsequently, it was time for a Jesuit school, then for college and university, a doctorate in law, and a job in a law office. From his early childhood, Otlet developed a great love of reading, of books, which had once successfully replaced his friends. Literature helped him cope with loneliness – Paul lost his mother when he was three years old.

At 23, Otlet met Henri Lafontaine, also Belgian and also a specialist in law, fascinated by the theory of data classification. This friendship would play an important role in the fate of both. Otlet and Lafontaine decided to join the Society for Social and Political Science, which allowed them to delve into bibliographic issues. Three years later, Otlet founded the International Institute of Bibliography.

Why did the two respectable, successful lawyers focus so much on improving the handling of what they had already found, organizing it, making it searchable, rather than searching for new information? Both were convinced that peace, as an alternative to war, was achievable when different cultures could exchange information without hindrance. It was necessary to create conditions in which access to any data would be as easy as access to any kind of weapon.

Mundaneum, or “World Palace”

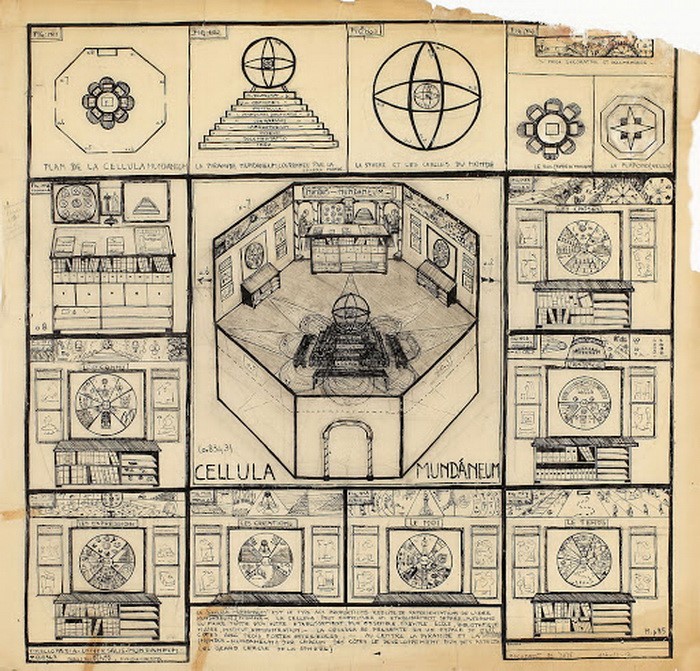

The purpose of the Mundaneum was to bring together in one place all human knowledge of the world. This new kind of global library was to be a tool available to everyone on Earth. Whatever question arose in his head – about political trends or the climate of Africa, exchange rates, a recipe for English pudding – the well-organized mechanism of the Mundaneum structure was to provide a quick answer.

All this is very similar to the way modern society lives, which has made computers and the World Wide Web part of everyday life.

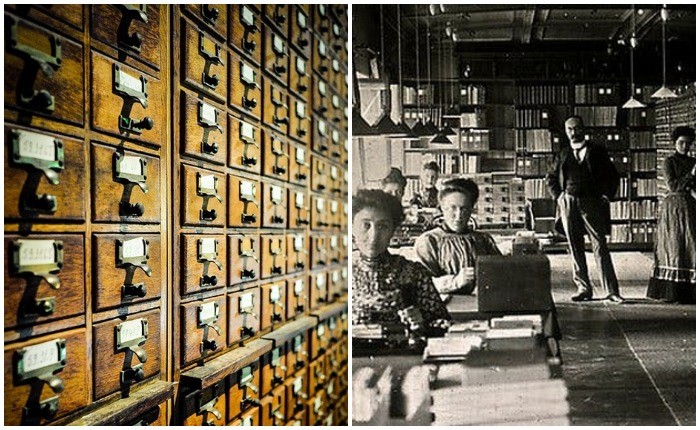

By 1910, the companions had received support from the Belgian government. A large room in the Park of the Fiftieth in Brussels – the left wing of a palace with dozens of halls – was allocated to house the data repository. And in 1920 the “city of knowledge” began its work. At the heart of the new enterprise were numerous boxes with cards – a total of 12 million indexes, as well as a repository of the press, thematic selections on various topics – an encyclopedic overview of all human knowledge. In the future, this archive was to become the centerpiece of a whole “city” of information, with a huge library and an International Museum.

A search service was also launched. A specially recruited staff of the Mundaneum accepted inquiries that came in by mail or telegraph. These letters were sorted, then searched for information, retyped, and sent back to the person who had sent them. The work required not only an enormous amount of human resources, but also an impressive amount of paper.

Completing the Mundaneum Project

Paul Otlet’s book, in which he described the principles of the computer, even if not yet using that name, saw the light of day in 1934. But the time for the development of such initiatives was over. By 1934 the Mundaneum had lost state support and the German troops occupying the country disposed of the palace of the “city of knowledge” in their own way: its halls were now home to an art exhibition of the Third Reich.

Both Paul Otlet and Henri Lafontaine passed away before the end of the Second World War, and the Mundaneum project was not to be revived. The remains of the archives were moved from one building to another several times until Professor Rayward of the University of Chicago became interested in them. The scholar, who did his dissertation on the activities of Paul Otlet, set out to revive the memory of the Mundaneum.

In 1998, after several years of work in the Belgian town of Mons, the Mundaneum museum was opened, where the atmosphere of the beginning of the last century was reproduced and all the work that was once done for the “paper Internet” was illuminated. By the way, in 2012, the museum and Google announced cooperation – so highly appreciated was the role of the Belgian “Mundaneum” in the development of the global information system. Now it sounds commonplace, but not so long ago it seemed something unexplored. Can a modern person imagine his life without an essay checker? Probably not! We can only thank the ingenious inventors who initiated a huge scientific breakthrough.

In addition, more recently, 20 years ago, the electronic knowledge system that the science fiction writers wrote about and that Otlet foresaw – Wikipedia – appeared

Add Comment